Chinese encroachment into Tibet has finally yielded a trump card, and it’s one India can seemingly do little about.

In July 2020, India and China fought a bloody skirmish in the Himalayas that left 20 Indian soldiers dead, according to unconfirmed reports.

Relations between the two countries have been strained in recent years, particularly after a standoff in 2017 involving the strategic Doklam plateau, control of which is necessary to cut off India from millions of citizens living in the country’s northeast.

The latest flashpoint to arise in the Himalayas is the Galwan river valley, a rocky and unforgiving ground with little in strategic value aside from commanding the high ground.

While tensions have been managed so far, India may be drawn into further skirmishes along its northern border with new details of China’s strategy for India and the region by 2035.

Published on the People’s Republic of China government website, the Section 14, Chapter Two’s heading reads “Expanding investment space”.

It elaborates, “To promote the construction of major projects such as new infrastructure, urbanization, transportation, water conservancy […] while implementing […] the development of downstream hydropower of the Yarlung Zangbo River.”

This serves as an effective indication that China will go forward with a long-held plan to build the world’s largest dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River, which flows north into the Indian Brahmaputra river.

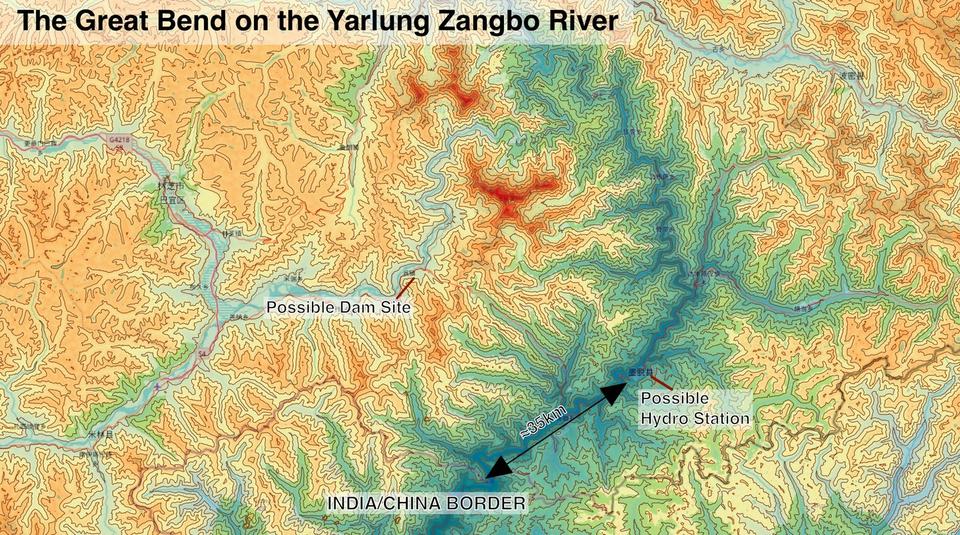

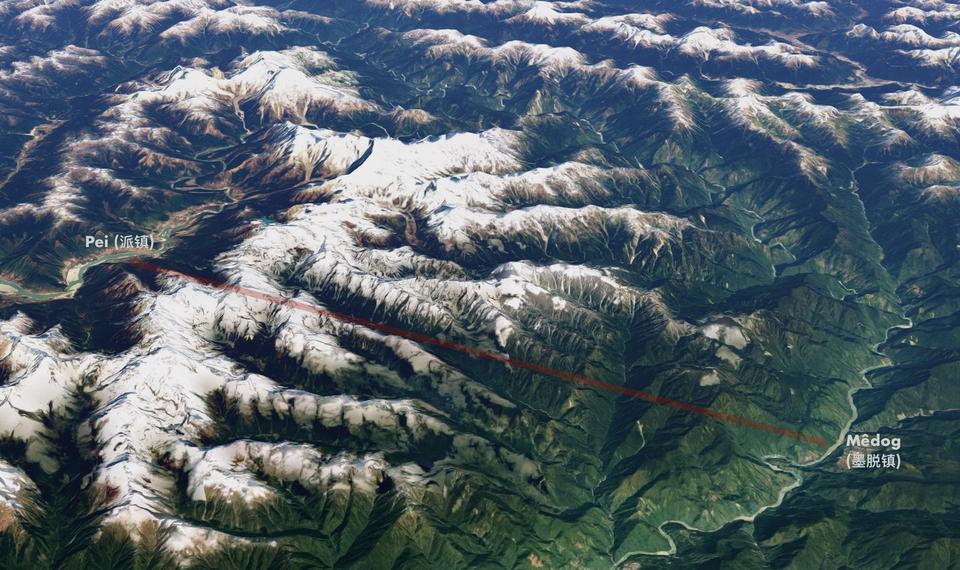

Geopolitics aside, the river is ideal for generating hydroelectric power. Along one stretch, colloquially referred to as “The Great Bend”, the river reverses the direction of its flow. At this crucial junction, water falls nearly 2,250 metres from China into India.

Harnessing gravity and the incredible force of the river could see any dam become an extremely productive hydroelectric endeavours.

China’s Three Gorges Dam, considered the largest dam in the world, is expected to be surpassed in energy output by the newly proposed plan by three times over. The construction of the Three Gorges Dam saw over 1.4 million people displaced.

The new dam is expected to produce at least 60 gigawatts of electricty. To put that into perspective, one gigawatt is the amount of energy captured by 3.125 million solar panels or 412 wind turbines. One gigawatt is also enough to power 110 million LED lights.

The river is fed by melting glaciers, and mountain water run-off, flowing through the Himalayas, China, India and Bhutan to supply an estimated 1.8 billion people.

Few details are available regarding China’s plans for the dam’s construction, aside from older proposals that suggest building a massive power generation tunnel with a turbine, using entry and exit points that would radically affect the river’s flow.

To realise this, China would have to build a dam upstream in the river, ensuring that cities south of the entry point may be flooded as close as 35 kilometres away, requiring the evacuation of hundreds of thousands.

The expected upstream impact is mild compared to what people downstream of the intended dam can expect. The Brahmaputra river delivers much of the water used by India’s northeast. More dangerously, at least 60 percent of Bangladesh’s population relies on its catchment basin.

A catchment or basin is an ecological system of drainage that sees rainfall or river water drained into the surrounding environment, and can be accessed through lakes, wells or smaller tributary rivers.

While over half of the river’s total catchment falls in Chinese or Tibetan territory, it’s unclear how much of the water’s flow begins in China. That’s significant, because it determines how much water China will effectively deny its neighbours downstream.

One study estimates that water flow originating from China ranges between 7 to 40 percent, the disparity between the two explained by seasonal changes. In effect, this would leave India and Bangladesh fully reliant on China’s largesse. During dry seasons, they would depend on China’s release of water, while during monsoons, they’d depend on China regulating the amount of water sent downstream to avoid floods.

Is China allowed to do that? Under international law, countries that are upstream of a river have the sovereignty to build dams on their stretch of water, even though it may impact countries further downstream. However, the right is balanced by the principle of ‘reasonable use’ and ‘no harm’.

China certainly claims to adhere to this, with press releases emphasising mutual trust and cooperation on water. The fact remains however, that China is not a party to the UN Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes.

More concerningly, China has previously cut access to water for countries downstream, as recently as 2019.

During one incident, China cut water from its Jinghong Dam, which fed the Mekong river. The result was a significant loss of water in Thailand as it struggled with drought. In January 2021, water was cut again, with notice delivered days after the cut took place.

For India and Bangladesh, the internal rhetoric used by China is equal cause for concern.

“It will be a historic opportunity for the Chinese hydropower industry […] it is a project for national security, including water resources and domestic security,” said Yan Zan Zhiyong, Chairman of Power Construction Corp of China, speaking to a state-affiliated newspaper.

The admission gives rise to concerns that the securitised dam could be used as a means to further China’s ends. This could permanently restrain India in confronting Chinese encroachment, with the ever-present threat of droughts or floods.

More dangerously, water to the river could be cut entirely, though not without some measure of internal displacement. For China, this is the ultimate trump card, and one India has no means of countering short of pre-emptive action or concerted international pressure.

There are other risks too. The Himalayan mountains were geologically created with the buckling pressure caused by India and Eurasia’s tectonic plates. The region is still tectonically active, with massive energy released regularly in the form of earthquakes.

In 50 years, the region saw four major 7.8 to 8.7 Richter scale earthquakes occur, which would pose structural dangers to any dam in the area. Two of the earthquakes historically took place in the same proposed site of China’s new dam.

The collapse of a dam would come at a significant toll in human life and destroyed infrastructure for India and Bangladesh. Because the dam would be situated at the edge of its border, China would face few risks.

Once construction begins and given the size of the project, China is unlikely to stop until it sees it through, making concrete any tensions or risk of conflict in the region.